Spiritual Ecstasy: Israeli Spirituality in the Days of Jesus the Messiah, by Kevin Williams

Were Pharisees opposed to anything supernatural?

[Author’s Note: The following text is neither an endorsement nor a censure of Jewish mysticism as practiced today or during the biblical era. Rather, it is an attempt to present the facts of a multi-faceted and ancient religious philosophy in a short, manageable format for the Pneuma Review.]

Mysticism today connotes different things to different audiences. For some, it embodies the “New Age” movement, bordering on—if not leaping over—the edge of witchcraft. For others in more traditional forms of Christianity mysticism is ingrained into their culture, and rumored now again in the media with a crying icon or the silhouette of the Madonna “witnessed” on the side of a building or ink stain. In their faith, this expression of mysticism confirms their religion. C. S. Lewis, a committed Anglican, wrote: “The true religion gives value to its own mysticism; mysticism does not validate the religion in which it happens to occur” (Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, page 65).

Mysticism today connotes different things to different audiences. For some, it embodies the “New Age” movement, bordering on—if not leaping over—the edge of witchcraft. For others in more traditional forms of Christianity mysticism is ingrained into their culture, and rumored now again in the media with a crying icon or the silhouette of the Madonna “witnessed” on the side of a building or ink stain. In their faith, this expression of mysticism confirms their religion. C. S. Lewis, a committed Anglican, wrote: “The true religion gives value to its own mysticism; mysticism does not validate the religion in which it happens to occur” (Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, page 65).

For our purposes, we are going to have an introductory examination of Jewish mysticism and its effect—if any—on the Christian faith. “Introductory” because with volumes of commentary on the subject spanning thousands of years, and us with only these few pages, an introduction is the best for which we can hope.

Perhaps, though, this introduction will motivate some to explore the subject further. For those I offer one piece of advice: do so prayerfully, leaning ever on the Holy Spirit so that, “He will guide you into all the truth” (John 16:13). When examining Jewish mysticism, all that glimmers is not gold. While it may appear attractive and “spiritual,” it may or may not actually be so. Paul teaches us that a “partial hardening has happened to Israel” (Romans 11:25). Partial is not a full hardening, neither is it full spirituality. There is gold and there is fools’ gold. Use wisdom so that you are not led astray.

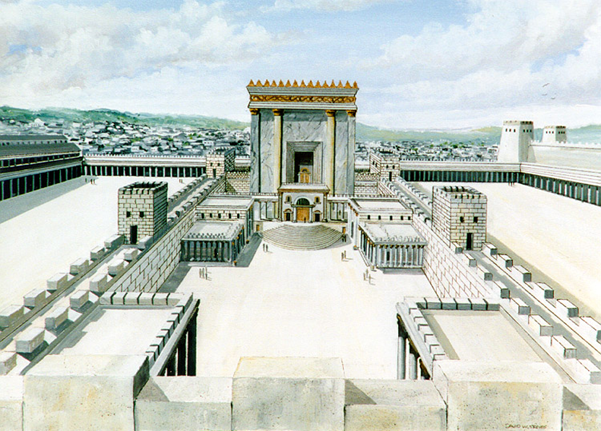

The heading, Spiritual Ecstasy, was not an easy title upon which to settle for this article. Today, “ecstasy” brings with it negative connotations of illegal narcotics and sensual innuendo. However, to allow modern base behaviors to hijack a word does not change the fact that in the age of the second temple in Jerusalem, what we might call spiritual expression or charismata, was in those days known among the Hebrews as “Spiritual ecstasy.” Though many today have divorced the very concept that Jewish men and women in the days before, during, and following Jesus’ atoning incarnation believed in or practiced any godly form of spirituality, the recorded history says otherwise, and the term “spiritual ecstasy” appears frequently in the ancient extra biblical texts.

Similarly, this “spiritual ecstasy” has continued in certain circles of Jewish orthodoxy today. In what might be considered a paradox, those with the most religious fervor—in the sense of strict adherence to the Pentateuch and a complex code of oral traditions—do believe in and pursue what they refer to as “Spiritual ecstasy.” From their perspective, both now as well as in the ancient observances, anything that comes into contact with the divine must somehow transcend its mundane nature—including mankind.

So it is with this intention in mind that the title Spiritual Ecstasy is employed as an attempt to maintain continuity with the understanding of some of our fellow heirs of Father Abraham—the Jewish people.

Category: Church History, Fall 2005, Pneuma Review