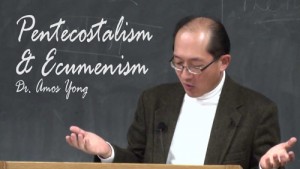

Pentecostalism and Ecumenism: Past, Present, and Future (Part 2 of 5) by Amos Yong

Amos Yong challenges classical Pentecostals to re-examine what ecumenism really is.

II. Classical Pentecostal Objections to Ecumenism

Given this biblically defined ecumenism [Editor’s note: please see part 1 in the Winter 2001 issue], then, why is it that most Pentecostals remain staunchly anti-ecumenical? While many reasons have been given, three stand out as representing a fair consensus. First, Pentecostals believe that the unity of the Church should be understood spiritually rather than visibly. Second, many Pentecostals believe that the ecumenical movement represents churches that have betrayed the essence of the gospel, especially doctrinally. Finally, correlative with the previous objection, Pentecostals are generally concerned that non-Pentecostal churches are devoid of the life that is found only in the Spirit of God as ‘pentecostally’ experienced and defined, thus fulfilling the biblical prophecy of widespread apostasy in the last days. Let me respond to each in order.

Objection 1: Spiritual rather than visible unity

Pentecostals have always valued the spiritual unity that they have found in the experience of the charismata, especially speaking in tongues. Manifestations of tongues and other spiritual gifts are, for them, a more incontrovertible sign of the Spirit’s presence and activity in their lives and congregations. The institutional, organizational, and architectural forms of non-Pentecostal churches do not impress Pentecostals. These are considered to be merely outward signs of pomp and circumstance that all human constructions can display, but which do not guarantee inward and spiritual vitality. Rather, these outward paraphernalia are symptomatic of the hierarchicalism, patriarchalism, and traditionalism endemic to the history of the church, all of which has been conveniently covered up or obscured by stain glass windows, Gothic architecture, and iconography that is distracting at best and bewitching at worst. The point is that the unity of the church is found, not in outward forms of organization and agreement, but in the spiritual togetherness that genuine Christians experience through the Spirit in the name of Jesus.

A brief response proceeds along three lines. First, Pentecostals should recognize that this argument actually has its roots in the Reformation and post-Reformation era and is driven by an ideology of individualism. The basic assumption is that God works first and foremost through individuals and not institutions or organizations. Just as sola Christus neglected the Holy Spirit, sola fide neglected sanctifying works, and sola Scriptura neglected the role of tradition in reading and interpreting the Word of God, so did the unspoken emphasis on the individual neglect the centrality and importance of the community of faith. Since the Reformation, the Church has been struggling to counteract the influential but exaggerated importance of Luther’s “here I stand!” A myriad of individuals after the German reformer have come to similar conclusions regarding their parent Protestant churches and movements resulting in the emergence of innumerable denominations.

Category: Ministry, Pneuma Review, Spring 2001