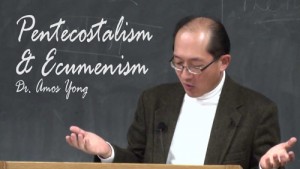

Pentecostalism and Ecumenism: Past, Present, and Future (Part 4 of 5) by Amos Yong

Amos Yong challenges classical Pentecostals to re-examine what ecumenism really is.

IV. Pentecostal Ecumenism: A Survey

If it is true to say that Pentecostalism has always been ecumenical, it is also true to say that in certain respects, the ecumenical movement has always been “pentecostal.” In what follows, I want to tease out three elements of what I call “pentecostal ecumenism” wherein central features of Pentecostalism are highlighted. These include the missionary thrust of the modern ecumenical movement, its concern for charismatic unity, and its emphasis on what I call the “diversities of the Spirit.” Let me comment on each in order.

Missionary Pentecostal ecumenism

Few Pentecostals today realize that the ecumenical movement was initially launched as a missionary movement, and in many respects retains that focus today. As missiologists and historians have noted, while the twentieth was the century of Pentecostal missions, the nineteenth was that of the Protestant missionary enterprise. It was during the nineteenth century that what we now call the mainline churches established themselves on every continent. It was also during this same time that problems were identified, many of which were far too large for the mission agencies of these individual churches and denominations to resolve on their own. The heart of the modern ecumenical movement was thus birthed at a global mission conference which convened at Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1910, and from which the International Missionary Fellowship (IMF) was established in 1921. Meanwhile, it was realized that missionary work could not proceed apart from confronting both the social and political injustices prevalent during the inter-war years and the doctrinal differences that separated the churches. Thus emerged the Life and Work world conference (1925) and the Faith and Order world conference (1927). These combined to form the WCC in 1948.16 In 1961, the IMF officially joined forces with the WCC, thus re-affirming the WCC’s commitment to the missionary witness of the churches.

I am getting ahead of the story without having made my point which is this: the early twentieth century was a time during which churches in the West awoke to the power of ecumenical unity for carrying out the task of the Great Commission. As the various churches began to assess the daunting project of world evangelization, they realized that such could be accomplished much more efficiently if they worked together rather than separately. In short, it was the missionary endeavor that brought hitherto self-sufficient groups, movements, and denominations together. I should not need to point out that the central impetus toward Pentecostal organization was also the collaborative power of common mission. Fulfilling the missionary mandate has done more to bring the Church together since the Reformation than anything else.

Category: Fall 2001, Ministry, Pneuma Review