Which Way the Trolley: America’s Hot Wars During the Cold War, Part 2

In Part 2 of “Which Way the Trolley: America’s Hot Wars During the Cold War,” William De Arteaga continues to challenge assumptions and asks if the Korean and Vietnam Wars could have been Just Wars.

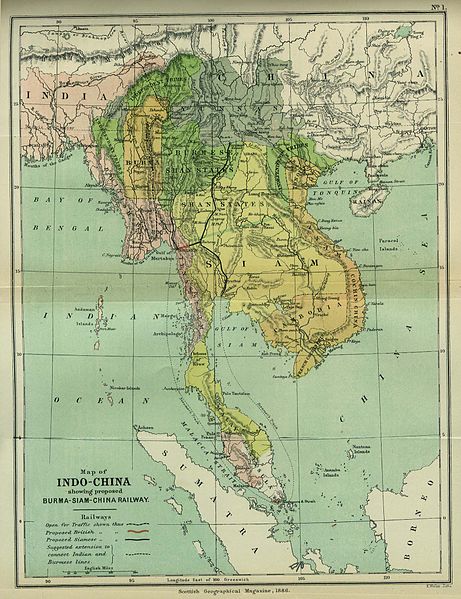

The Indochina Wars

1886 map of Indochina, from the Scottish Geographical Journal.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

The First Indochina war (1946-1954) began right after the end of WWII as the French tried to reclaim their Empire in Indochina (Laos, Cambodian and Vietnam) after having ceded it to the Japanese. French forces quickly regained control over most of the area. Indo-Chinese nationalists, led by Ho Chi Ming, did not like the idea much and began a guerrilla resistance. This moved from guerrilla warfare into a combined guerilla and set-piece battles after the Chinese Communists triumphed over their Nationalist enemies and arrived at the Chinese-Vietnam border (1949). Chinese and Soviet supplies and weapons, including artillery and anti-aircraft guns flowed south to the Viet Minh Communist army.[1]

The French Army fought with determination, while slowing losing home support. The French had several major victories, but the Viet Minh were persistent and won a major battle at a crossroads called Dien-Bien Phu (1954). After that, a newly elected French socialist government negotiated a peace. In that settlement France left Indochina, with South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia under local, non-Communist rule, and the North ruled by the Communist Viet Minh.

The treaty allowed the civilian population of Vietnam to go to the area they deemed best, and this resulted in a mass migration of several million Vietnamese Catholics fleeing from the North and into South Vietnam. They did so fearing Communist persecution, which had already been fierce against Catholics in Communist China.

The Communist Viet Minh capture the French headquarters after the Battle of Dien-Bien Phu.

After the division of North and South Vietnam the Emperor of South Vietnam was overthrown by a coup engineered by his own premier, Ngo Dinh Diem. He was Catholic and ruled the majority Buddhist country autocratically and with the Catholics as his base of support. Unfortunately, his regime was allied with the land-holding class, and would not further land reform (as happened in China). These factors ultimately created major difficulties when warfare resumed.

What the American public calls the Vietnam War should really be called the Second Indochina War, because it was fought not only in Vietnam, but in also Cambodia and Laos. American Green Berets and CIA backed groups struggled in Cambodia and Laos against the increasingly well-armed Communist armies in those nations.[2] Under President Nixon, the US Army made an incursion into Cambodia to destroy supply bases that were feeding Viet Cong forces.

The Communist cadres which had remained in place in every town and village in South Vietnam since the partition rose up in insurgency in 1960. President Kennedy, who had suffered a defeat in his handling of the Cuban Bay of Pigs invasion, did not want to lose another country to Communism under his watch, and sent in advisors to help stiffen and support the South Vietnamese Army.

Kennedy was continuing the Truman-Eisenhower policy of the containment of Communism. He was much junior to both Truman and Eisenhower, but shared with both the belief that opposition to Communism was a duty. His inaugural address (January 20, 1960) was a graceful, poetic expression of American anti-Communism and its sense of crusade that had earlier been proclaimed by President Truman.

Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans – born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage – and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world.

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose and foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.[3]

After Kennedy’s assassination, President Johnson continued this policy. He increased the number of advisors and quantity of materials supplied to the South Vietnamese. But the Communist Viet Cong insurgents and the North Vietnamese continued to gain the upper hand. Like Truman before him, Johnson was forced to a decision to either see another country fall into Communist hands or intervene directly with American ground units. He chose to intervene. Also like Truman, he chose not to declare war, but relied on the American public’s strong anti-Communist sentiments to support the war.

Category: Church History, Winter 2017