The Kingdom and the Power, reviewed by Jon Ruthven

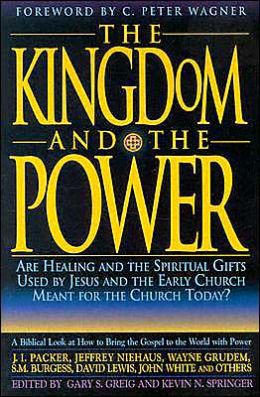

Gary S. Greig and Kevin N. Springer, eds., The Kingdom and the Power: Are Healing and Spiritual Gifts Used by Jesus and the Early Church Meant for the Church Today? A Biblical Look at How to Bring the Gospel to the World with Power (Regal Books, 1993), 463 pages.

Gary S. Greig and Kevin N. Springer, eds., The Kingdom and the Power: Are Healing and Spiritual Gifts Used by Jesus and the Early Church Meant for the Church Today? A Biblical Look at How to Bring the Gospel to the World with Power (Regal Books, 1993), 463 pages.

Thirty years ago, when I graduated from a prominent evangelical divinity school, I prayed long and hard for a book like Kingdom and the Power to answer the objections that my seminary professors had raised against my Pentecostal experience. My parting shot from the seminary was a tutorial research paper that eventually evolved into my doctoral dissertation and later, book, On the Cessation of the Charismata. The cessationist professor read only about half of the project, assigned it a “B” and refused to dialog about its arguments and exegesis. At the same time, a close friend and fellow student with normally high grades, who is now the New Testament Professor at Edinburgh, fared even worse: he received a “C” on his thesis, “Signs and Wonders in the New Testament.” There was little discussion on the ideas presented, aside from an assertion from one committee member to the effect that along with Jehovah’s Witnesses and Mormons, Pentecostals should not have been allowed enroll at that school.

Times have changed since the 60s. The shrinking proportion of evangelicals who still maintain that spiritual gifts have ceased with the apostles are much more willing to dialog—if only because increasingly they now find themselves in a theological Alamo, where there are constant defections and increasing apathy on the part of the defenders. In the last decades, the debate over the gifts of the Spirit has become much more sophisticated exegetically and theologically. Many non-charismatic evangelicals today seem to be more willing to receive, or at least read, the new exegetically-grounded works of Pentecostals and charismatics.

The Kingdom and the Power is a work that represents a theology in transition from categories framed by traditional Protestant theology to ones more naturally expressed in scripture. Accordingly, Kingdom effectively avails itself of the breadth of scholarship from the last 60 years (see especially, pp. 24-28) as the numerous endnotes will attest, though without compromising the authority of its biblical grounding. The work presents itself as a polemic against critics of the Third Wave renewal generally, and cessationism in particular (p. 16). More significantly, the book’s extended scholarly argument represents a long step toward a comprehensive theology for the movement. Kingdom moves beyond its theological polemic, “Exegetical and Theological Studies,” in Part I, to Part II, to express its pastoral concern involving real-life application to ministry, and, in Part III, toward contributions from the disciplines of history, psychology, social anthropology and missiology. Seven appendices treat narrower issues dealing principally with cessationism.