Roger Olson: Don’t Hate Me Because I’m Arminian

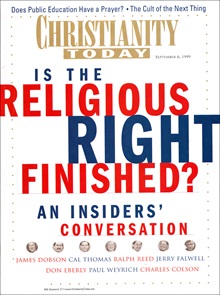

September 6, 1999 issue of Christianity Today

Roger E. Olson, “Don’t Hate Me Because I’m Arminian: My Reformed friends sometimes treat me like the enemy, but actually we need each other,” Christianity Today (September 6, 1999), pages 87-94.

Many remember the schism between George Whitefield and John Wesley as a microcosm of the debate between Calvinists and Arminians. Roger E Olson points out that although they made up before they died “ . . .their disagreement has lived on in American evangelicals’ waxing and waning debates about sovereignty and the doctrines of election and free will” (p. 87). He says that the unity enjoyed by the post-World War II evangelical coalition is beginning to wane with more and more Reformed Scholars, like R.C. Sproul and Michael Horton, questioning whether an Arminian can be a genuine evangelical. Horton goes as far as to say “An evangelical cannot be an Arminian any more than an evangelical can be a Roman Catholic” (p. 87).

Olson defines Arminians as “Protestants who deny unconditional election and affirm resistible grace” (p. 87). He further states “I hope for a new détente between those of us who believe in the soul’s ability to cooperate with regenerating grace (Arminians) and those evangelicals who believe that regenerating grace must precede even repentance and faith (Calvinists)” (p. 87).

Roger E. Olson is the Foy Valentine Professor of Christian Theology and Ethics at the George W. Truett Theological Seminary of Baylor University.

Olson contends that the two sides of this great debate need each other. Though he had been taught from youth that Calvinists were practically heretics, a turning point came for him when at the funeral of a relative a Reformed pastor “… preached one of the most evangelical sermons I had ever heard. He challenged all present to give their lives to Jesus Christ … cognitive dissonance finally broke out into complete rebellion against the anti-Calvinist polemics I had heard from Pentecostal leaders and teachers” (p. 90). Though he still did not hold to Calvinist doctrine, he realized that the “… tent of authentic evangelical Christianity was bigger and broader than I had been led to believe” (p. 90). Olson began to see that though there is not much middle ground in the debate (e.g. Cal-minians) they could certainly learn from each other’s emphases. “I was convinced that the evangelical community needs both George Whitefield and John Wesley, and that their heirs need one another to achieve the beauty of balance” (emphasis his, p. 90).

Working among many Reformed theologians, Olson learned that many equated Arminian with semi-Pelagian, a heresy named for a fifth-century British monk named Pelagius, who taught that men were born innocent and therefore could initiate salvation. Informed Arminians are quick to point out that they do not believe man can initiate salvation, for he is spiritually dead. They hold that God moved first through prevenient or enabling grace, which allows the sinner to make a decision to accept or reject the gospel.

Category: Ministry, Spring 2000