Cautious Co-belligerence? The Late Nineteenth-Century American Divine Healing Movement and the Promise of Medical Science

In the days of Pasteur and Lister, was the Divine Healing movement out of touch with what American society believed about medicine?

Introduction

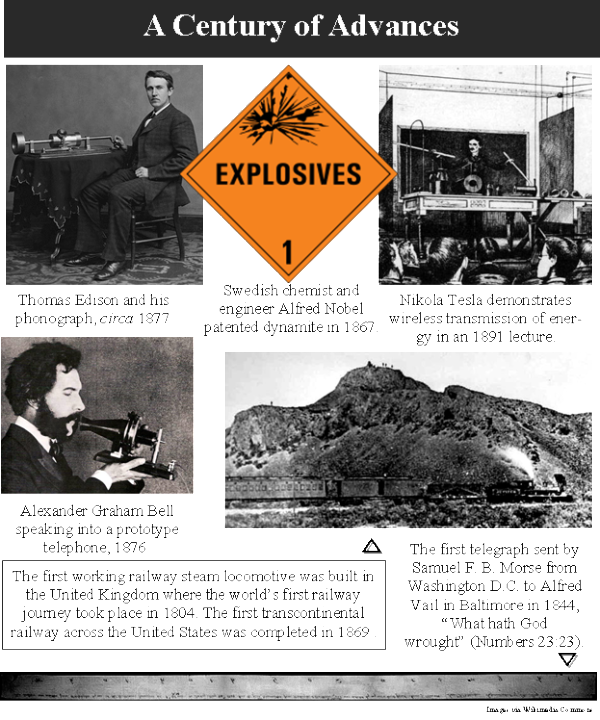

The late nineteenth century was a time of monumental change. It witnessed a cyclone of transformation and progress rivaling, at least, that of any preceding era. Not surprisingly, it was a time of key advances in medical science. This era was home to Pasteur, Röntgen, Lister, and a number of lesser known, but still significant, medical pioneers. These inventors and their discoveries radically reshaped and significantly advanced the practice of medicine. New advances seemed to be dawning with every new day. At the end of the nineteenth century, the promise of medical science seemed unlimited.

At the same time, the late nineteenth century also saw religious change. There was the emergence of the Divine Healing movement, a loosely associated group of religious teachers and practitioners who sought to promote and practice the healing power of the indwelling and resurrected Christ over that of natural means. This movement gained tens of thousands of adherents in a significantly short span of time. Key figures in this group included people from a wide-variety of denominations, men and women, ministers and physicians. Furthermore, this movement played an essential role in the birth of Pentecostalism,1 the greatest religious movement of the twentieth century.

Therefore, there rose simultaneously on the American landscape at least two significant approaches to health and healing in the late nineteenth century, each with its own biased and ardent champions and devotees. Yet, the opinion of the late nineteenth-century Divine Healing teachers did not, as one might expect, thoroughly dispense with the value and goodness of physicians, their diagnoses, and medical treatment. While they did not completely dismiss the advances, usefulness, and propriety of medical science, they did assert that it was, at best, a deficient approach to the gravity, complexity, and depth of human disease. While they believed that physicians and their medical treatments may be gifts from God, they were convinced that medical science was fundamentally unable to bring to humanity the kind of health and life intended for them by God and found solely in the redeeming work of Jesus Christ.

This chapter will explore those common and key responses—both the affirmations and the denials—of the late nineteenth-century Divine Healing proponents to the growing popularity and use of medicine, remedies, and physicians.

Divine Healing Affirmations of Medical Science

Almost to a person, Divine Healing advocates readily granted that doctors and many of their treatments exist by the providence of God. A. B. Simpson, founder of The Christian and Missionary Alliance, noted that physicians and their medical treatments are “among God’s good gifts” to humanity.2 Charles Cullis, the renowned Boston homeopath and father of the Divine Healing movement in the United States noted the “valuable” role that doctors and their treatments may play and continued his own homeopathic medical practice in harmony with his ministry of Divine Healing.3 Carrie Judd Montgomery, one of the Divine Healing movement’s more celebrated authors, speakers, and founder of the “Home of Peace” in Oakland, California, granted the skill of those physicians that worked with her during her own infirmity.4 One lesser-known figure, Kenneth McKenzie, a member of Simpson’s Christian and Missionary Alliance and author of no fewer than two significant texts on the theology and practice of Divine Healing, noted that only those with an immature theology of Divine Healing and “extremists” would deny that there is good in doctors and medicine.5 Furthermore, the fact that most Divine Healing proponents continued to refer to physicians as “Dr.” shows that only by caricature could one assert that Divine Healing movement saw absolutely no good or use in consulting with physicians and implementing their prescriptions.6

These affirmations of physicians and medical treatment by Divine Healing proponents, however, were not blanket endorsements. Rather, as we will see, they were limited to particular and specific arenas. What is particularly interesting is the seeming unanimity of the Divine Healing proponents in regard to those particular areas that they affirmed in regard to medical science. Almost universally, the Divine Healing teachers affirmed three separate but related aspects of the goodness of physicians and medical science: 1) the recent and substantial advances in medical science, 2) the physicians’ ability to diagnose the physical cause of disease, and 3) the physicians’ occasional ability to alleviate symptoms of disease.

Category: Church History, Summer 2010