Cautious Co-belligerence? The Late Nineteenth-Century American Divine Healing Movement and the Promise of Medical Science

Affirmed the Recent and Substantial Advances in Medical Science

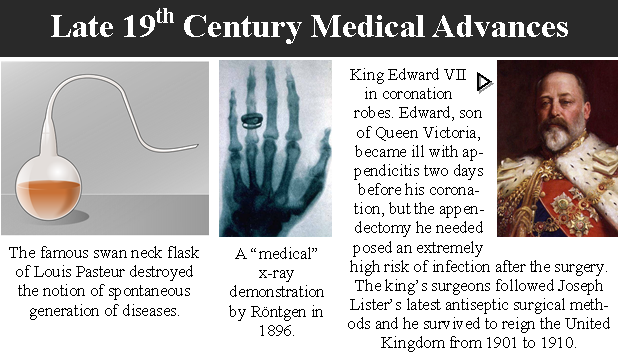

The nineteenth century, as noted earlier, was a time of significant progress in the realm of medical science—advances not always appreciated by the religious establishment. The Divine Healing proponents were not so biased, however, as to deny that there were any real and worthy developments. Observing that the general progress in knowledge was a fulfillment of Daniel’s prophecy,7 Simpson also noted, “The progress of medical science in the past half century has been phenomenal. No fair-minded person can refuse to concede its value, notwithstanding all its limitations, counterfeits, and failures.”8 On another occasion, he called recent scientific progress “radical and astounding.”9 Cullis, in defending to the local authorities his establishment and placement of a “Cancer Home” in Boston, cited the recent progress in medical science as that which made the presence of such a home no real threat to the surrounding population.10 These advances, though, were not without scrutiny and criticism. One of the advances, for example, that Simpson questioned was the developing medical science of eugenics that alleged that disease in all of its manifestations could, at the very least, be significantly limited by the legislated and selective breeding of humanity to do away with “the imperfect product.” He described such a program as “foolishness with God.”11

Affirmed the Physicians’ Ability to Diagnose the Physical Cause of Disease

Second, the Divine Healing teachers affirmed physicians’ ability to often accurately diagnose the physical cause of disease. This affirmation, though, was more often implicit than explicit. R. Kelso Carter, a noted professor, author, and composer (he wrote the hymn “Standing on the Promises of God”), while eventually pursuing an avenue of physical restoration other than medicine, at no point doubted that the diagnosis his doctors gave him of “incurable heart disease” was accurate.12 Montgomery never questioned that she suffered from spinal fever as her physicians had diagnosed.13 Cullis often relied on his own medical training and expertise to identify the particular physical distress of those who came to him and trusted implicitly the diagnosis of others in the medical profession.14 A. J. Gordon, noted author, educator, and pastor of the Clarendon Street Baptist Church in Boston, asserted that physicians are those who have the “ability to interpret … the laws of health to the sick” and implies that they are right to do so and may do so rightly.15

Adoniram Judson Gordon, named after the famous missionary to Burma, founded the Boston missionary school that would become Gordon College. “It seems clear from the Scriptures that it is still the duty and privilege of believers to receive the Holy Spirit by a conscious, definite act of appropriating faith, just as they received Jesus Christ” (The Ministry of the Holy Spirit, 1894).

One example of particular interest is found in Simpson’s discussion of the cause of the death of Jesus Christ. In order to make a theological point, Simpson appealed to the opinion of contemporary physicians, diagnosing across the centuries and relying on the biblical accounts, regarding the cause of Jesus’ death. He noted that many physicians attributed the death of Jesus, medically, to a “rupture of the heart. He did not die from the ordinary causes incident to crucifixion, but He died from a spasm that caused His heart to burst.”16 Simpson not only leaned on the diagnosis of contemporary physicians of an event centuries previous but cited them as authoritative and accurate on an issue as theologically significant as the crucifixion.

Affirmed the Physicians’ Occasional Ability to Alleviate Symptoms of Disease

Third, the Divine Healing proponents affirmed the medical community’s ability to occasionally alleviate, if not eliminate, symptoms of disease. In his later retraction of one aspect of his earlier Divine Healing assertions, Carter noted that the actual practice of the key proponents of Divine Healing shows that, while their rhetoric may seem to leave no room for the use of natural means, each of them both prescribed and practiced the use of natural means.17 Such is most evident in the life of Cullis who never relinquished his medical practice and continued to think of and identify himself as a member of the medical community with a practice, at least to a great degree, founded on the use of natural means.18 Montgomery, speaking about the malady from which she was eventually divinely healed, did note that often her grandmother’s “old-fashioned home remedies” afforded her some level of comfort and relief as did the medication provided by physicians19. Gordon affirmed the “recuperative forces of the natural world.”20 Even Simpson, who so strongly warned against the use of medicine, granted its “limited value” and cautious employ.21 The Divine Healing proponents noted that, by divine providence, there was woven into the very fabric of creation some level of medical relief. The goal and practice of physicians was to identify these recuperative, “mechanical” powers of nature and apply them to those in need.22 Some of the proponents called the employment of this recuperative power of nature which existed by the purposeful, beneficent, and creative power of God, the vis medicatrix naturae.23 As it was part of the providential structure of creation, it should not be rejected, as far as it went, and may have been the best help that some could obtain.24

It should be noted that one of the internal debates between the Divine Healing proponents concerned whether or not one could legitimately ask God to give his blessing to the use of means. Implicitly, the very discussion shows that, to varying degrees, each side admitted that natural means may bring about some measured effects, at least. If there were no effects, the question of blessing is, at the very least, much less pressing.

Category: Church History, Summer 2010