The theology and influence of Karl Barth: an interview with Terry Cross

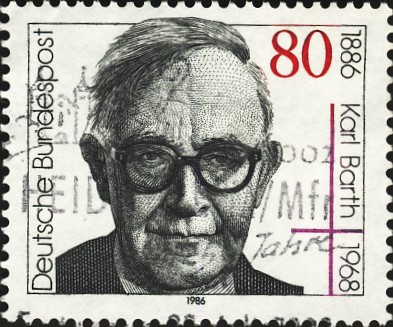

Karl Barth was an influential Swiss Reformed theologian that lived from 1886 to 1968. Featured on postage stamps and the cover of Time (April 20, 1962), today we would call him a rock star among theologians. A strong critic of those Christians who supported the Nazis, Barth is best known for his involvement in the neo-orthodoxy movement and writing Church Dogmatics. PneumaReview.com speaks with Terry Cross about why Barth remains so influential and what church leaders should glean from his prolific writings.

Karl Barth was an influential Swiss Reformed theologian that lived from 1886 to 1968. Featured on postage stamps and the cover of Time (April 20, 1962), today we would call him a rock star among theologians. A strong critic of those Christians who supported the Nazis, Barth is best known for his involvement in the neo-orthodoxy movement and writing Church Dogmatics. PneumaReview.com speaks with Terry Cross about why Barth remains so influential and what church leaders should glean from his prolific writings.

PneumaReview.com: You have been working with the theology of Karl Barth for many years. What has drawn your long-term interest?

Terry Cross: I began reading Barth seriously in 1980 while working on the MDiv thesis. I was comparing Karl Barth and the evangelical theologian, Carl Henry, on their views of revelation. Henry was quite adamant about some of Barth’s errors in relation to the Word of God—as were a number of evangelical scholars. However, when I actually read Barth himself, I realized that the caricatures made of him by many evangelicals did not hold water. Barth actually said in numerous places the direct opposite of what Henry thought he said. I began to wonder, ‘If Henry can read this incorrectly, what else has been written by Barth that deserves closer attention?’ That started my journey through the 13 volumes of the Church Dogmatics. It also fueled the flame to learn German well enough to read Barth in the original language he wrote. Over and over I have discovered that rather simplistic thumbnail sketches of Barth’s ideas on any one theological position have missed the complexity and nuance of Barth’s own words. In addition, as a Pentecostal theologian I became fascinated with some of Barth’s ideas as related to Pietism and, by extension, to Pentecostal thought. For example, in Church Dogmatics I/1, Barth expounds his idea that the Word of God has a threefold form—Jesus Christ (Word in flesh); Scripture (Word in writing); and Preaching/proclamation (Word of God in preaching/teaching). Barth has a rather “occasionalist” view of what occurs. The Scripture, for example, becomes the Word of God but may not be the Word of God (in some fundamentalist sense) because such equation of God’s Word in revelation with written Scripture can make the Bible into a “holy” book that has almost magical qualities instead of a record that becomes God’s Word when God’s Spirit enlivens it to our hearts. Indeed, Barth is the only theologian I know who has a pentecostal-like theology of preaching: our human words are taken up by God’s Spirit and are made clear and powerful as it becomes the Word of God to individual believers in the community of faith. In many ways, this seemed reminiscent to me of the high respect for preaching that Pentecostals have whereby a “word” from the Lord becomes clear and really rings true when the Spirit drives it home in our hearts.

PR: Some argue that Barth was the most important Protestant Theologian of the Twentieth Century. Do you agree?

Terry Cross: Barth is the only theologian I know who has a pentecostal-like theology of preaching: our human words are taken up by God’s Spirit and are made clear and powerful as it becomes the Word of God to individual believers in the community of faith.

Terry Cross: Yes, I do. While others have had long-lasting impact from the 20th century (e.g., Tillich, Bultmann, Reinhold Niebuhr, Juergen Moltmann), Barth’s herculean shift of the balance of the weight off of the old Protestant liberalism of his professors (like Harnack and Herrmann) that signaled the immanence of God in human lives and onto a view of the transcendence of God in which God is entirely other than humans. The old liberal school had proposed that Jesus taught a valuable morality that we should follow, but was not divine. For them, God’s Spirit was to be equated with the human spirit—the human personality. Faith, then, was some psychological commitment that connected on a deep emotional level with God. Into this situation that seemed to glorify humans, Barth became frustrated with the easy manner in which his German professors rushed to support Kaiser Wilhelm going to war in 1914. Barth was a pastor in a small village in Switzerland at the time (Safenwil) and gave himself totally into the socialism of the day, working as the “red pastor” in assisting laborers to form unions and more equitable wages. By 1915, his excitement for socialism began to run dry and his theological source for preaching was no longer effective. Into this setting in 1915, Barth and his close friend (a nearby pastor named Thurneysen) began to study Scripture again, but this time not through the lens of historical criticism or psychological critique of the authors. They studied the book of Romans, all the while Barth wrote his thoughts about each verse in a notebook. In a later lecture, he described this encounter with Scripture as a “new world of the Bible.” What was this? He tried to listen to and read Scripture as if God himself were speaking to him today from this long-ago text. The result was a vivid freshness of his preaching and interpretation. Some called this a “pneumatic exegesis” because of the emphasis on the Spirit but also because of his sense that the Spirit operates with the text and with the hearer. The freshness of letting God be transcendent and speak to the Church through the Scriptures today was so powerful that one theologian described his commentary on Romans as a “bomb on the playground of theologians.” Instead of starting theology from the human dimension and attempting to build one’s way up to the divine (a la Schleiermacher), Barth began theology from the divine dimension and asked what God was saying to us through his revelation. While some folks during the decade of the 1920s called Barth’s theology “dialectical,” Barth himself preferred to speak of it as “a theology of the Word of God.” Almost singlehandedly Barth turned the theological trajectory away from the old Protestant liberal school of thought to a new, fresh way of viewing God that tended to sound more like the Protestant Reformers of the 1500s. To be even more precise, some felt they saw in Barth a simple rehashing of old Protestant Scholastic Orthodoxy of the 1600s and 1700s. For this alone, he could be considered an important theologian of the 20th century, but add to that the depth of his understanding of the connections between Christology and various doctrines as well as his dogged determination to keep Christ as the center of the revelation of the triune God and we have someone who is not only innovative and interesting, but paradigm-setting for the future of the theological task.

Category: In Depth, Summer 2015