The Making of the Christian Global Mission, Part 4: Charity Invites Change

Christian historian Woodrow Walton continues his investigation into the origins of the modern movements that inspired Christians to go and share the mission and message of Jesus throughout the world.

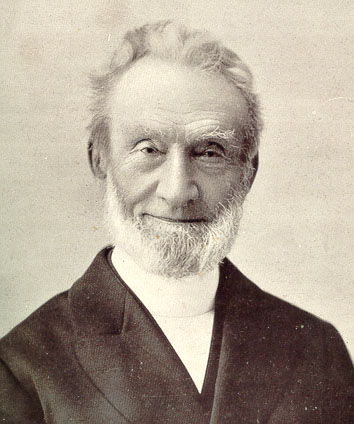

George Müller

When studying how living out the gospel changed the social fabric of the early nineteenth century England, Europe, and North America, several figures must be considered. How their charitable work thrust the gospel into the societies of both England and the young United States of America should not be forgotten or underestimated.

The first of these was George Ferdinand Muller [also spelled Müller or Mueller], who was born in Kroppenstedt, Kingdom of Prussia (now Saxony-Anhalt Germany) and later moved to England. In 1829, Muller offered to work with Jews in England through the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews. He gained his fame as a man who cared for 10,024 orphans during his life time and provided educational opportunities for them. He not only preached the gospel but also established 117 schools which offered Christian education to more than 120,000 children. In England, he associated himself with the Pilgrim Brethren Church. He and his wife, Mary Groves, had four children, two of which were stillborn.

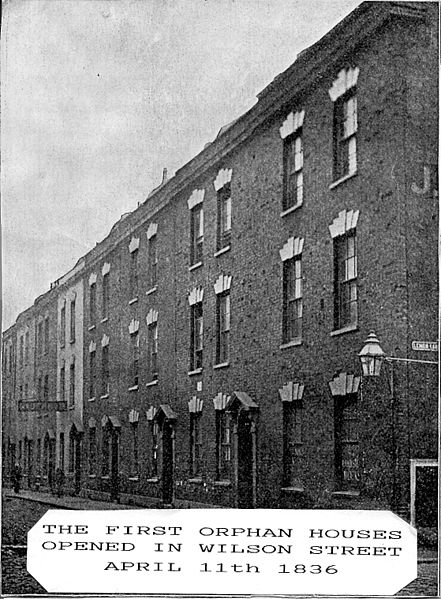

The New Orphan Houses in the Ashley Down district of Bristol, England.

Image: The George Müller Charitable Trust/Wikimedia Commons

Muller, after early bouts of illness, and the death of his wife, in 1871 married again. His second wife was Susannah Grace Sanger. Together, beginning in 1871, they began a 17–year period of missionary travel that took them to the United States of America, Canada, Germany, India, Australia, Palestine, the Straits of Malacca, and New Zealand. When in the U.S.A., he was welcomed by the President of the United States of America. He died at the age of 93 on March 1898 and has been honored throughout the world ever since as the director of the Ashley Down orphanage in Bristol, England and the care of 10,024 orphans over the years, and as man who never asked for support for his work but when support was given by churches and individuals, he kept account of it and wrote “Thank You” letters to every donor. His example defies any estimate.

This article is part of The Gospel in History series by Woodrow Walton.

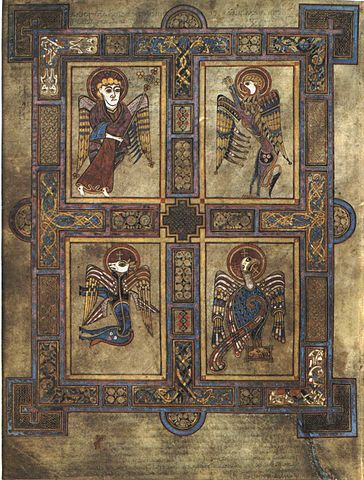

Image: The Books of Kells by way of Wikimedia Commons.

Simultaneous to the years of Muller’s life was the ministry of Frances Willard, the founder of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which challenged the liquor industry in the countryside and urban areas of both the frontier and growing cities. Willard was not only a stalwart defender of women’s rights but also one of the earliest of Christians to see the mission of God within the socio-cultural context and thus living out the ministry of Jesus as spelled out in the tenth chapter of the gospel of Luke. At the same time the Society of Friends and many of the Mennonites and Moravians were binding the wounds of soldiers and were given exemption from military service and recognized as peace churches, an exemption which exists into the present.

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard (1839 –1898).

Image: Gamaliel Bradford (1919) Houghton Mifflin Company/Wikimedia Commons

Simultaneously in this era the Congregationalists, Baptists, Dutch Reformed, and Methodist churches established schools for Native Americans. After a childhood of abuse and impoverishment, William Apess [originally spelled Apes] served as a soldier in the United States army during the War of 1812, became a Christian and entered into the ministry of the Methodist Church. He rose to fame as a preacher and as a lecturer giving protest of the plight of Native Americans in New England and beyond. His autobiography, A Son of the Forest, published in 1829, was the first published by a Native American writer. In 2014, Philip F. Gura, with the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, wrote a biography of William Apess. This writer owns a copy of Gura’s The Life of William Apess, Pequot. During the years of both his ministry and his series of lectures, he gained support from churches outside of the Methodists and public recognition. Slowly but surely, co-operation among churches of Arminian and Reformed backgrounds brought them together in different areas of Christian ministry and mission outreach.

Jesus’ great commission was being realized as a missionary mandate.

The Pietists had great impact within the colonies from the time of the Great Awakening and into the Second Great Awakening. In time, their influence was to lead to the formation of the Free Methodist Church, the Evangelical Free Church, and others who broke from synodical and presbyterian polities common among the Lutherans and Reformed Churches. It is against this background that Alexander Campbell during the Second Great Awakening welcomed any one of any Christian persuasion to participate in the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. We are all “disciples of Christ,” he proclaimed. Barton Warren Stone, the “New Light Presbyterian” felt much the same but simply used the term “Christian” no matter a person be Baptist, Presbyterian, Catholic, Lutheran, Moravian, Quaker, or Mennonite. The Anglican Church in America dropped the term “Anglican” from it vocabulary and re-named itself “Episcopal.” The Methodists in America under the leadership of Francis Asbury and others shortened their identity from “Methodist Episcopal” to simply “Methodist.”

Christian mission: evangelism and also outreach to rectify social ills.

In 1826, the American Society for the Promotion of Temperance was formed. However, there were many precursors of such public charity, many from the earlier years of the Christian faith. Basil of Caesarea initiated the first hospital for the sick and feeble. In the Middle Ages, the Beguines, a laywoman’s ministry initiated in the pre-Reformation era, reached out to the neglected, the homeless, the lame, and the poor, and wrote devotional and theological works which made for conflict with some of the “professional” clergy. But of great significance to the Reformation era and the years of the global expansion of the gospel was the initiation of Sunday Schools by Hannah Ball in High Wycombe of England in the late 18th century but carried further by Robert Raikes in 1780.

Robert Raikes the Younger (1736 –1811) promoted the Sunday school movement, raising awareness of a need for public education before state-run schools existed.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

The start of the Sunday Schools began with a school for boys in the slums. Raikes had been involved with boys incarcerated at the count Poor Law which was part of the jails at the time. Raikes believed that vice would be better dealt with school as a preventive and held on Sundays as the boys were frequently enlisted to work in factories the other six days. The best available teachers were among the laity of the churches. The basic textbook was the Bible. The originally intended curriculum began with learning to read the Bible and then progressed to the catechism of the Anglican church. The first Sunday School class started in July of 1780 in the home of a Mrs. Meredith with boys and then extended to girls. By 1782 several other Sunday Schools opened around Gloucester, England.

On November 3, 1783, Raikes published an account of the Sunday Schools in the newspaper he started. Later news of the spread of the Sunday Schools appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine and by 1784, a further account of the spread of the Sunday Schools appeared in a letter to the Arminian Magazine.

The missionary mandate included healing the sick, discipleship, and helping the afflicted and the down-trodden.

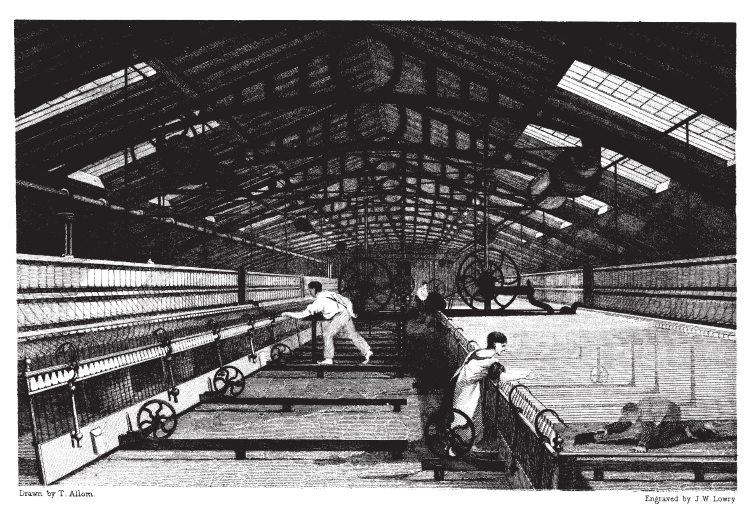

Children laboring in a cotton spinning factory in 1835.

Image: illustration from The History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain (1835), by way of Wikimedia Commons.

Little by little, Jesus’ great commission was being realized as a missionary mandate that was greater than proclamation and fulfilled the whole missionary made enunciated by Jesus and recorded in Matthew 25:35-40; 28:18-19; Luke 10:2-9; 18-20; and Acts 1:8, and universalized in Mark 16-18. The missionary mandate included healing the sick, discipleship, and entering the domain of the “serpent” to release the imprisoned, the afflicted, the haunted, the down-trodden,” and penetrate the darkness of the world with the light of a greater kingdom not of this world but of the one who is King of Kings and Lord of Lords.

PR

Category: Church History, Winter 2021