Spreading from the Frontiers: Another Look at the Gospel in the Medieval Church

Wars without end, daily terror, displacement of entire populations: Can the medieval Church help us understand how to respond to our troubles today? What relationship should there be between the Church and political power? What should we make of how monks lived out their understanding of the good news of Jesus on the margins of society? How can we come to grips with how crusaders often acted nothing like Christ whom they claimed to be fighting for? Christian historian Woodrow Walton shows how the Gospel spread from the frontiers in this re-appraisal of the years A.D. 400-1452.

This article is part of The Gospel in History series by Woodrow Walton.

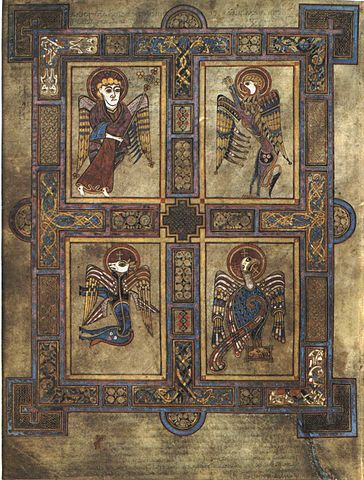

Image: The Books of Kells by way of Wikimedia Commons.

What transpired from the time of the Gothic and Vandal invasions of Eastern and Western Europe between A.D. 400 and 1452 is little different from what is occurring in our 21st century world. We complain about the threat of ISIS and the troubles of our global society, including the troubles of the United States of America. Yet those basic troubles are the same as what was experienced for a thousand years between A.D. 400 and 1452. Christians were as troubled then as we are today, but the Church survived then and it will survive this.

As the invasions forced Christians to flee from the Mediterranean world, which included all of North Africa and the Near East, into the frontiers of northern Europe, the British Isles, the Sahel belt, the northern mountains of Africa, and the further northeastern and eastern extremities of Eurasia, so are we witnessing the extension of the Church in southern and central Africa, South America, and the Far East by way of exiles. Orthodox Christians native to western and central Asia are coming into the United States of America and are welcomed in by such organizations as Solidarity with the Persecuted Church, BarnabasAid, and the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service. As renewal arose from the frontiers so are we finding renewal by displacements of populations.

The Church in those years, between A.D. 400 and 1452, went through a restructuring process with both positive and negative effects upon the life of the Church. One of the most puzzling features was the relationship between the Christian community and the political order. The Roman system of government in western Europe crumbled under the Gothic tribes, the Vandals, and Lombards but the Church had the structure to withstand the onslaughts. When the Arabs spread throughout northern Africa, the churches re-located themselves in the British Isles. There were two after-effects. Since the Church had the organization it re-read Augustine’s magnum opus, De Civitate Dei (The City of God), written at the time of the Vandal Invasions of Mauritius, Lybia, and the African coast and took a triumphalist approach where the Church had a hand in influencing the political order. The Church in the East suffering from the over-reaching powers of the emperors at Constantinople saw in Augustine’s City of God, a spiritual authority apart from the political order. There were positive results from both approaches but there were negative ones as one. The West institutionalized the Church alongside that of the new political orders which took the place of Rome. Even when the Reformation took place in the 1500’s, Church and State stood side by side insuring the safety of each. Not so in Greece, Eastern Europe, and Western Asia. The Orthodox had no central structure. In each country, the Orthodox conducted their concerns through conciliar means but within the context of patriarch who had a pastoral oversight within each individual country. Rather than a pope, the patriarchs had to contend with the new political entities as best they could. Those in the Near East, Western Asia, and the West Coast of India maintained their identities but had a dhimmi status and were considered as second-class citizens within the Moslem and Indian worlds.

The Church in Western Europe and then in America never fully understood what Augustine was getting at.

Category: Church History, Spring 2017