Knowledge with Zeal: Biblical Examples of Using God-Anointed Intellect in His Service

Paul

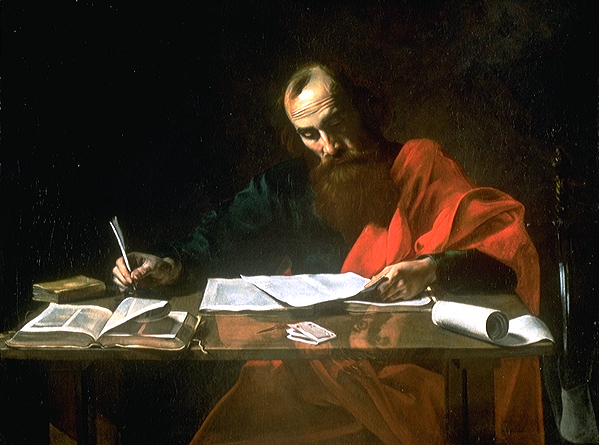

Paul Writing His Epistles, probably by Valentin de Boulogne (1591 – 1632).

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Paul was from Tarsus in the province of Cilicia which was in the southeastern part of Asia Minor (Acts 21:39). As a border province and a commercial center, people from Tarsus would have not only been aware of the Hellenic culture that permeated the Roman Empire, but would have also been well aware of the religious thought to the east. E.M. Blaiklock notes that this cosmopolitan atmosphere was an ideal environment for nurturing one who would become God’s messenger to the Gentiles.17 Since God’s revelation came first to the Jews, it would require the mastery of the Old Testament, but it would also require the intellectual ability to communicate that message in the thought forms of the Greek speaking world.

Tarsus was a university city, home of the renowned teacher, Athenodorus, the personal tutor of Caesar Augustus, who returned home in his later years. Unlike other cities, such as Alexandria, it was the natives of Tarsus, not those from outside, who flocked to the schools.18 Blaiklock is surely correct in contending that it was a great learning opportunity for a brilliant mind like Paul’s, and a choice place of preparation for becoming an apostle to the Gentiles.19

Although the Jewish enclave in Tarsus was tolerant of Hellenic culture, Philippians 3:4-11 reveals that Paul was raised in a strict Hebrew home.20Paul’s claim to be a “son of the Pharisees” in Acts 23:6 may indicate that his father or one of his other ancestors may have been associated the Pharisees.21 Gerald Hawthorne notes that the phrase “a Hebrew of Hebrews,” (v. 5) refers either to Paul being of completely Jewish lineage, or that he was raised to speak Hebrew in the home.22 Perhaps both were true, although Bruce holds that Aramaic, not Hebrew, was Paul’s native language.23 Paul was most likely fluent in both of these languages as well as Greek. Paul’s fluency in Hebrew would have been critical to his studies under Gamaliel, his inclusion as a member of the strictest sect of the Pharisees (Acts 22:3), and his ability to exegete the Old Testament in its original language.24

His rabbinic training under Gamaliel in Jerusalem would likely have commenced shortly after his Bar Mitzvah which took place when he was thirteen.25 Gamaliel, a prominent member of the Jewish Sanhedrin, was “an honored teacher of the law” (Acts 5:34). According to R.F. Youngblood, Gamaliel believed that the Law was divine, but tended to emphasize its human elements, calling for a more relaxed application of the Sabbath laws, and urged kindness towards the Gentiles. He was also an avid student of Greek literature.26 Paul’s knowledge of Greek literature seems to be consistent with that of his mentor, suggesting that Gamaliel’s attitude may have help to shape his own.

By far, Gamaliel’s greatest influence upon Paul was in relationship to the Law of God. According to Paul’s own confession, he was of the strictest sect of the Pharisees, meaning that he was passionate about the study and adherence to God’s Law (Philippians 3:5). Like many others, perhaps he assumed that salvation was obtainable through obedience to the Law. Paul’s Damascus Road experience resulted in a change in perspective regarding the function of the Law (Galatians 3:24), but not his desire to study and fulfill it. When Paul speaks of counting all things in his background as loss or rubbish, he was only discounting these things as a way of salvation (Philippians 3:8-9). He was not devaluing education or intellectual development. Jesus himself rightly criticized the Pharisees for many things, but the pursuit of mental acumen was not one of them.

In assessing whether Hellenism or Judaism had the greatest influence on him, one is compelled to note that Judaism held the stronger hand.27 Paul’s deep intellectual understanding of the Old Testament is reflected throughout his writings and in the speeches recorded (and edited) by Luke in Acts. As to his writings, the book of Romans is unsurpassed in reflecting the depth and range of his theological thinking, especially in regards to his reinterpretation of the function of the Law as a means to lead one to Christ and not as the means of salvation in itself—a radical departure from Judaism (Romans 7 and 8). Mainly didactic in nature, Merrill Tenney notes that while Romans does not contain all fields of Christian thought, “it does give a fuller and more systematic view of the heart of Christianity than any other of Paul’s epistles, with the possible exception of Ephesians.”28 Romans can be described as a well reasoned defense of the Christian faith.

Category: Biblical Studies, Spring 2008