Jesus and Jewish Prayer

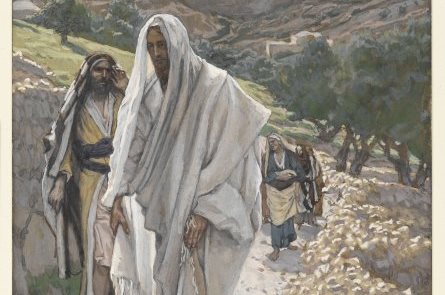

Some Jewish leaders during the Second Temple period argued that Christ’s acknowledgement of God as אבא was a blasphemous claim of divine sonship, and a lack of reverence for the Lord (Mark 14:60-64). This assumption is false because Jesus was a Hebrew who was required to learn the ways of Yahweh through his training of the Torah (Luke 2:46). As a result, Jesus highly respected the Almighty. Yet, this did not negate his deep affections for the Father. By understanding the Father’s role in his life, Christ was aware that God would forgive the transgressions of those who would ask.[11] Additionally, Charles M. Laymon states that Jesus understood that God was the “[R]uler…[and] [C]reator of the universe.”[12] Both of the themes of God as ruler and Creator correlate with the reverent view of God that was commonly held by the Jews of the Second temple period. Therefore, Christ revered the Father.

In the Lord’s prayer, Jesus invites his disciples to the idea of “kinship” (Matt 6:9b). The fact that Jesus, as the Christ, was the fullness of God in human form does not negate his Jewish heritage and shared culture that formed and shaped his values as a man. Although Jesus possessed a unique relationship with God as his son, it did not discount the distinct relationship between God and his people. In fact, Jesus’s sonship enabled the Jews to view their relationship with the Father from an intimate, childlike perspective, as opposed to a fearful servant’s perspective. Thus, Christ’s affectionate address to the Father served as an invitation to kinship.

In the Lord’s prayer, Jesus invites his disciples to the idea of “kinship” (Matt 6:9b). The fact that Jesus, as the Christ, was the fullness of God in human form does not negate his Jewish heritage and shared culture that formed and shaped his values as a man. Although Jesus possessed a unique relationship with God as his son, it did not discount the distinct relationship between God and his people. In fact, Jesus’s sonship enabled the Jews to view their relationship with the Father from an intimate, childlike perspective, as opposed to a fearful servant’s perspective. Thus, Christ’s affectionate address to the Father served as an invitation to kinship.

The Role of a Father in the Jewish Culture

Throughout the Jewish culture, fathers played a crucial role in the lives of their children. Brad H. Young observes that fathers in the Jewish culture served as “…a loving and caring figure…” in the household.[13] Jesus taught his followers that the Father was a loving and caring figure through his teaching of the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32). After asking for a share of his father’s estate, the prodigal son sold the piece of property and spent his earnings on a reckless lifestyle. Shortly afterward, famine struck the nation, and with no money left over, the prodigal son had to take a job as a servant in order to make ends meet. Realizing the luxurious lifestyle he had left behind on his father’s property, the prodigal returned home, and confessed his sin before his father. Rather than condemning his son for his actions, the father embraced him and welcomed him home. Throughout this parable, there was a recurring theme of repentance. The motif of repentance was especially significant for the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, or the Day of Atonement. According to Peter Ochs, prayer during these Jewish holidays was centered around the concept of “…returning [to the Lord].”[14] The idea of “returning” for the Jews in the Second temple period originated in the commandments of the Torah that intended to turn them away from sin and turn back to obey Yahweh’s commands (Neh 1:9). By incorporating this theme into their prayers, the Jews would take on the role of the prodigal son by returning to the Father with an attitude of repentance.[15] As a man who grew up as a Jew and was trained in the customs and culture of Second temple Judaism, Jesus grasped the fact that penitence was central to the Jewish faith. Not only that, but he also understood that the Father was a loving and caring figure who was ready to forgive those who would simply return to him. For this reason, Jesus taught his followers to ask the Father to forgive their sins by integrating contrition into his prayer (Matt 6:12).

Category: In Depth, Summer 2016