Jeffrey Overstreet: How I Got “Dead Poets Society” Wrong: And how a great professor changed my mind

Rob Wilkerson resonates with a recent article.

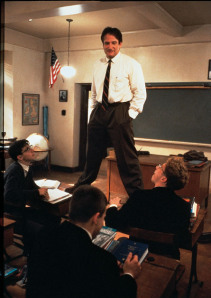

Robin Williams as Mr. Keating in Dead Poets Society

Jeffrey Overstreet, “How I Got Dead Poets Society Wrong: And how a great professor changed my mind” ChristianityTodayOnline (September 16, 2014).

Overstreet’s article brought back memories. A lot of them, to be honest. To some degree, the feelings the movie evoked returned to me like I saw it yesterday.

First, there were the memories of how I felt as a high school graduate, the same year the movie was released. I remember identifying intensely with Keating, a mentor every kid wished was his dad. I remembered thinking how much of Neil was in me, both the joyous freedom to be me, mixed with the insanity of conformity to cultural norms and standards.

Second, there were memories of how I felt about rules and standards. Growing up on the legalistic side of Christianity, I could understand the concerns of Neil’s father and Keating’s administration. Rebellion is built into every fiber and DNA strand of every human being. This was probably true of me when I watched it. The movie was like a pinball inside my soul, thrashing around, ringing bells, sounding noises, while smacked by the paddles of my legalistic upbringing and the taste of free grace.

Third, there are memories of my parenting. I’m a father to four awesome kids. Too often I’ve parented like Neil’s father. At least, that’s what I fear. More often I’ve wanted to parent like Keating, loosening the ropes, the guides of culture (including Christian culture) from the fragile sapling of grace I saw growing inside my children. Overstreet said it best. “Looking back at authority figures who have inspired my respect, and at those who have been driven by ego and a desire to control, I’ve come to suspect that anyone who seeks to instill character in another person by force will produce an equal and opposite reaction.”

There is a root found in both men in this movie. It is fear. Plain and simple. Neil’s father was fearful that his son wouldn’t fit into his tiny little world, that his son would find a type of happiness that he had talked himself out of years earlier. He was fearful of freedom, so he couldn’t let his son enjoy it. Then there’s Keating. Overstreet believes that “Mr. Keating models a healthy balance of freedom and responsibility. He descends into that world of order, accepting the form of a servant, and makes all things new. He shows them what the imagination, taking the shape of love, makes possible.” Perhaps. Probably. But undoubtedly obvious in Keating, as well as in his real life character, was this tinge of immaturity.

Category: Living the Faith, Summer 2014