Historical Development of Wesley’s Doctrine of the Spirit

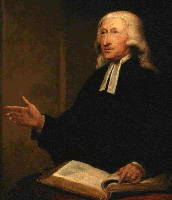

Although John Wesley had spoken about the Holy Spirit prior to 1738, it was not until after Aldersgate that he began to develop a distinct pneumatology. Aldersgate was not Wesley’s conversion-initiation; rather it was largely a pneumatological experience of the “internal witness of the Spirit.”1 His ‘heart strangely warmed’ marked a theological shift from outward works toward an experiential focus on the Spirit. He continued to develop this focus on the role of the Holy Spirit in Christian experience throughout his life. One can trace the role of the Spirit in the three distinct stages of Wesley’s thinking; early, middle, later.2

The purpose of this article is to demonstrate that there is a recognizable development of Wesley’s doctrine of the Holy Spirit, which began to take form at Aldersgate and continued to be developed throughout his lifetime. This article will begin by briefly looking at the role of the Holy Spirit in each of the three stages of Wesley’s life and at the corresponding sermon corpus. This research will lead to an analysis of the various influences on the development of Wesley’s pneumatology. In addition, there will be an evaluation of the various ways in which the Holy Spirit played a role in his overall theology.

The Early Wesley 1725-1738

As mentioned earlier, there are three distinct stages of Wesley’s theological development. The early Wesley refers to the time between his ordination as a deacon on September 19, 1725 to his Aldersgate experience on May 14, 1738. Many scholars believe that 1725 marked the beginning of John Wesley’s religious awakening and the first of three phases in his theological development.3 He began to think seriously about entering the Church and his parents enthusiastically encouraged him. During this time several major things helped shape Wesley’s religious thought. Wesley came into contact with Bishop Jeremy Taylor’s Rules and Exercises of Holy Living and Dying, Thomas a’ Kempis’s Christian’s Pattern, and William Law’s Christian Perfection and serious Call.4 These writings made a profound impact upon Wesley’s spirituality. They put him on the path toward inward holiness.

There is no telling what will happen when the church rediscovers Wesley’s doctrine of the Holy Spirit.

Another important development was that Wesley became acquainted with ancient Christian literature through the assistance of fellow John Clayton, who was a competent patristics scholar.5 Wesley’s love for the Eastern Fathers can be seen throughout his Works, particularly “Macarius the Egyptian” and Ephrem Syrus.6 He became convinced that their pattern of holy living was true and authentic Christianity. More importantly for this study, was the ancient Christian’s emphasis on the person and experiential work of the Spirit, which no doubt had an impact on Wesley’s thinking.7 These various influences made Wesley’s time at Oxford an important season of religious and theological development and no doubt sowed impressionable seeds, which would later develop into Wesley’s mature pneumatology.

“The Circumcision of the Heart” 1733

On January 1, 1733, at Saint Mary’s Oxford, Wesley preached “The Circumcision of the Heart”, which contains the basic elements of his soteriology. This sermon also says more about the Holy Spirit than any of his other sermons prior this time. However, it appears that he was still working out his understanding of the relationship of the Holy Spirit and his overall theology. He said that, “without the Spirit we can do nothing but add sin to sin,” and “that it is impossible for us even to think a good thought without the supernatural assistance of his Spirit as to create ourselves, or to renew our whole souls in righteousness and true holiness.”8 Wesley recognized early on that Spirit played a vital role in overcoming sin and living a holy life. He was also developing his doctrine of Christian assurance. It is important to mention that Wesley sought assurance long before Aldersgate. He said:

This is the next thing which the ‘circumcision of the heart’ implies-even the testimony of their own spirit with the Spirit which witnesses in their hearts, that they are the children of God. Indeed it is the same Spirit who works in them that clear and cheerful confidence that their heart is upright toward God; that good assurance that they now do, through his grace, the things which are acceptable in his sight; that they are now in the path which leadeth to life, and shall, by the mercy of God, endure to the end.9

Category: Church History