From Babel to Pentecost: Proclamation, Translation, and the Risk of the Spirit

Can postmodernism tell us something about how the church is to function, how we tell the story of Jesus, and how the Spirit works in our lives?

Postmodernism, The Church, and The Future

A Pneuma Review discussion about how the church should respond to postmodernism

The wind (pneuma) blows where it wishes and you hear the sound of it, but cannot tell where it comes from and where it goes. So is everyone who is born of the Spirit (pneuma).

John 3: 8

Can Jacques Derrida, a Jewish philosopher who confesses that he “rightly passes for an atheist,” possibly make any meaningful contribution to the understanding of Christian proclamation in the postmodern context?1 After all, is Derrida not the prophet of humanistic relativism or, worse, the Antichrist of textual meaninglessness? He most certainly approaches texts with the genuine suspicion that they are not always as objectively transparent as conservative readers may take them to be. He insists that a close reading of texts will always disclose places where they deconstruct themselves by calling into question their own assertions.2 Furthermore, he contends that every attempt to interpret the meaning of a text results in yet another instance of hermeneutics, which is to say, that interpretation always begets more interpretation. Of course, the authorized keepers of orthodoxy, those who defend religious certainty and objective biblical knowledge, fear that if one never escapes hermeneutics, but endlessly struggles with multiple interpretations without ever discovering the stability of cold, hard facts, then theology succumbs to only relativism and intellectual chaos. Certainly such Derridean suspicion should find no place in Christianity, in a religion predicated upon Jesus’ Great Commission to go forth and proclaim the truth of divine salvation. Consequently, Derrida’s “atheistic” philosophy must represent all that is religiously reprehensible in postmodern culture and cannot but be the enemy of Christian faith and proclamation.

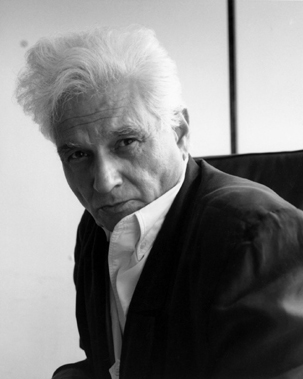

Jacques Derrida (1930-2004).

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Yet the depiction of Derrida specifically and of postmodernism generally as merely the most recent expressions of secular relativism and anti-religious pluralism might well be a misinformed caricature. I personally believe that to be the case. I disagree quite strongly with those who identify Derrida’s approach as destructive of Christian faith, hope, and love and as dismissive of the potentiality of language to communicate divine grace and theological knowledge. Indeed, nothing in his philosophy of language prescribes a rejection of God, truth, or meaning. As John Caputo, one of Derrida’s most careful and creative readers, states it, his postmodern perspectives display an “armed neutrality” toward personal faith and religious sensitivity.3 Derrida remains neutral with reference to the content of belief, neither affirming nor denying specific doctrines, while maintaining an armed diligence toward every human pretension to final and certain knowledge, toward the pretentiousness of becoming doctrinaire. That is to say, Derrida reminds us that we are finite creatures constantly seeking to comprehend existence from within the limited structures of that existence and, therefore, should constantly remain open to different interpretations and alternative experiences. Caputo goes so far as to label Derrida’s position as “religion without religion,” that is, as a genuinely religious position but not one reduced to a particular organized religion.4 It might well surprise his detractors when they discover that Derrida himself writes about a personal religion of which no one truly knows.5 He calls himself a person of prayer,6 argues for the necessity of faith,7 writes beautiful essays on forgiveness,8 speaks of the possibility of divine grace,9 and establishes much of his critical philosophy on close and respectful readings of both the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures.10

Proclaiming and Naming an Unnamable God

In many of his major works, Derrida carefully examines various biblical passages ranging from Genesis 22 (the sacrifice of Isaac) to Revelation 22 (the significance of Jesus’ second coming) and contends that one encounters a constant struggle in the Bible with the limitations of words and the impossibility of ever exhaustively explaining who God is and how God works in reality.11 The variety of biblical texts indicate for Derrida that theology, that is, words (logos) about God (theos) that seek to define God in appropriate ways, can never confine God within the restrictions of human concepts or rational principles. His position closely tracks that of Paul Ricoeur who notes that Scripture names God in multiple ways.12 For example, consider God’s own revelation of the divine name to Moses in Ex. 3:14. God responds to Moses’ request for the divine name by calling himself “Yahweh,” which means “I am that I am.” But this “name” is not a noun but a verb; it is a name that is no name, a “name” that leaves God nameless, as beyond the signifying power of any one sign. If this is the covenant name for God, the personal or proper name for God, then God’s name, Yahweh, means “the one who cannot be named.” One must confess, therefore, that every profession of God inherently speaks about God as the Unspeakable One and seeks to name God as the Unnamable One.13

Category: Ministry, Summer 2007