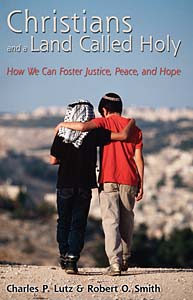

Christians and a Land Called Holy

Charles P. Lutz and Robert O. Smith, Christians and a Land Called Holy: How We Can Foster Justice, Peace, and Hope (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2006), 146 pages, ISBN 9780800637842.

Charles P. Lutz and Robert O. Smith, Christians and a Land Called Holy: How We Can Foster Justice, Peace, and Hope (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2006), 146 pages, ISBN 9780800637842.

Christians and a Land Called Holy is an appeal for action on the part of the wider Christian community in response to the vexing political situation in the Holy Land. This book was written in response to a visit of the authors to Israel/Palestine in 2002. They came away with a conviction that “Christian from elsewhere in the world have a faith-based interest in seeking a just peace between Israelis and Palestinians, and that they have a key role to play in pursuit of that peace” (ix).

Charles P. Lutz is a retired journalist who serves as Minnesota coordinator for Churches for Middle East Peace, a coalition of national church policy agencies. Robert O. Smith is an ordained pastor in the Evangelical Lutheran Church, who serves as Campus Pastor for the University of Chicago. Both have traveled often to Israel and regard themselves as emissaries for peace in the Holy Land.

The book is composed of two chapters each by the authors, an appendix featuring a short essay on the biblical politics of the Holy Land by Roman Catholic scholar Ronald D. Witherup, and a resource section with an annotated list of books, videos, and websites. The book also includes maps and twelve black and white photos.

The main argument of the book is that Western Christians should advocate for peace between Israelis and Palestinians. The authors state four reasons in support of their argument. First, peace would assure safe passage for Christian pilgrims. Second, the indigenous Christians of Palestine are “begging us to become active in their struggle for a secure and just peace” (ix). Third, Christian ministries in Israel/Palestine are disrupted by outbreaks of violence. And fourth, America Christians should engage in citizen advocacy with their government, which has influence over the conflicting parties.

In chapter 1, Lutz poses the question, “What’s So Special about This Space?” His answer is that the religious meaning of the land called holy is significantly qualified by the universalizing love of Christ, in which “all lands become equally holy” (20). Based on his conviction that the gospel has shattered the privileged geographic significance of Israel/Palestine, Lutz argues that Christians should be primarily preoccupied with securing justice and peace for all of its inhabitants, including Muslims.

The authors of A Land Called Holy are committed to the cause of peace in Israel/Palestine, however, their strategy for pursuing peace is flawed.

In Chapter 3, “Division in the Christian Family,” Smith assesses two opposing Christian views of state of Israel, evangelical Christian Zionism and mainline Christian Palestinianism. The former he denounces as indifferent to human suffering and the latter he upholds as the key to achieving genuine reconciliation and peace. Smith calls for a comprehensive strategy to accomplish “the marginalization of Christian Zionism it richly deserves” (80). He commends a recent appeal of the World Council of Churches for its member bodies to use economic pressures, such as disinvestment in Israel, to lobby against Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories.

Category: Living the Faith, Summer 2010