A Reflection on the Influence of Gordon Fee

By Rick Wadholm Jr, December 15, 2022

Gordon Donald Fee (May 23, 1934—October 25, 2022) arguably stands as one of the most widely known and influential Pentecostal scholars of the late twentieth to early twenty-first centuries. His works range broadly on topics of hermeneutics, translation, textual criticism, New Testament, Pauline studies, and theology (among other topics) and have been translated into numerous languages worldwide. Sadly, I only once was able to meet him in person for an all too brief conversation, though some of my family moved to Canada in the nineties specifically to study with Fee while he taught at Regent College in Vancouver, BC. The following are my own personal reflections on the writings of Fee that impacted my own life and calling and are neither comprehensive of his many writings nor intended as reflective of others’ experiences of his life and ministry upon themselves, but only an offering of one student of Scripture desiring to honor the legacy of another student of Scripture.

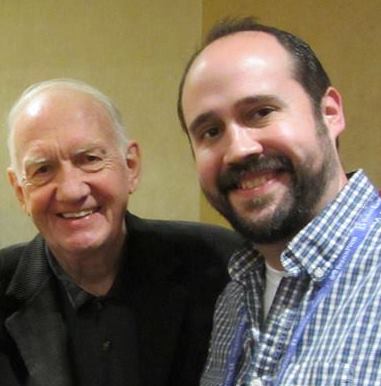

It was, in significant measure, owing to Gordon Fee maintaining ministerial credentials with the Assemblies of God, USA (AG) that I also received and maintain credentials with the same Pentecostal fellowship. He served as a constant reminder that the AG might be a broad tent among Classical Pentecostals to allow one (such as himself) to hold credentials even though Fee publicly diverged in writing on such issues as “initial physical evidence of the Baptism in the Holy Spirit” and the traditionally held Dispensationalist eschatology of the AG. It has not always been the case that Pentecostal scholars (in the AG or elsewhere) have been able to maintain such tensions. I thanked him in person for this testimony at a celebration of his life held by the Society for Pentecostal Studies at the joint meeting of the American Academy of Religion and Society of Biblical Literature in San Diego, CA, in November, 2014 (see below for video links to the archives on YouTube of this event).

It was, in significant measure, owing to Gordon Fee maintaining ministerial credentials with the Assemblies of God, USA (AG) that I also received and maintain credentials with the same Pentecostal fellowship. He served as a constant reminder that the AG might be a broad tent among Classical Pentecostals to allow one (such as himself) to hold credentials even though Fee publicly diverged in writing on such issues as “initial physical evidence of the Baptism in the Holy Spirit” and the traditionally held Dispensationalist eschatology of the AG. It has not always been the case that Pentecostal scholars (in the AG or elsewhere) have been able to maintain such tensions. I thanked him in person for this testimony at a celebration of his life held by the Society for Pentecostal Studies at the joint meeting of the American Academy of Religion and Society of Biblical Literature in San Diego, CA, in November, 2014 (see below for video links to the archives on YouTube of this event).

However, Fee did not always enjoy wide embrace by AG leadership. His views (some of those, for example, published in Agora: A Magazine of Opinion within the Assemblies of God) found him removed from the faculty of Southern California College (now Vanguard University), but he was never defrocked. This removal may precisely have been the opening needed for Fee among the wider Church in relocating to Gordon-Conwell. He was regularly challenged by AG leadership yet remained staunchly committed to the life of the Spirit and its proclamation in the church and academy globally. It was this commitment which encouraged me as a young pastor and emerging Pentecostal scholar to remain within the AG despite pressures against scholarship which seem to present themselves to those committed to the life of the church as part of the academy. Fee was a stalwart and potent example that one could indeed do this.

Fee’s scholarship demonstrated that one could be a Pentecostal practitioner and a scholar wrestling with the languages of Scripture and the manuscripts behind our translations and do this while maintaining faith in the God who inspired these texts.

Further, Fee contributed greatly to my sense of commitment to the study of ancient manuscripts and to not fear such historical critical inquiries—inquiries which had seemed to be something to fear in many of the contexts I had found myself growing up and in my early education. This was furthered when, in my first few years as a twenty-something year-old pastor, I read two volumes Fee co-edited with Eldon Jay Epp, New Testament Textual Criticism: Its Significance for Exegesis: Essays in Honour of Bruce Metzger (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981) and Studies in the Theory and Method of New Testament Textual Criticism (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1993). These two volumes suddenly opened to me the world of NTTC (and more broadly the work of textual criticism) that created an insatiable appetite to study more within the field. I found myself suddenly consuming the works on NTTC of Kurt and Barbara Aland, Bart Ehrman, Bruce Metzger, Daniel Wallace, and others on the OT, most particularly the many articles and publications of Emanuel Tov. I was preaching anywhere from 3-8 times a week and during my “free” moments reading every bit of these works I could find thanks to Fee’s inspiration. While I do not work professionally in TC I do teach on TC and have led many churches and classes on the topic as a way of addressing questions of faith and serious commitment to study of Scripture and faith. It has also meant that I have made several trips over the years to visit ancient biblical manuscripts in libraries and traveling museum collections as part of my love of the history of manuscripts and the preservation of Scripture.

As the young pastor tasked to preach for youth and adults many times a week I turned regularly to commentaries as learned companions to help in our congregation’s meditation of Scripture. Here I also discovered the help of Gordon Fee. The two commentaries which most impacted me were his commentaries on the Pastoral Epistles and 1 Corinthians: 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus (New International Biblical Commentary 13; Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1988) and The First Epistle to the Corinthians (New International Commentary of the New Testament; Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1987; Revised Edition: 2014). In the first of these, I found help for wrestling with the texts of Paul to two young pastors (and I needed that). I also found help in how to reconsider the words of Paul with regard to what seemed a silencing of women (something which seemed in my thinking to be out of sync with Paul’s ministry in the book of Acts). The egalitarian approach of Fee provided scholarship for my own pastoral concerns about the female members of Christ’s body and how they are also called and empowered by the same Spirit as co-equal workers and preachers of the good news of Jesus. In my reading of Fee’s (first edition) commentary on 1 Corinthians, two things (among many others) still remain firmly in my mind: (1) Fee’s proposal that the instructions regarding the silencing of women in 14:24-25 was perhaps an interpolation into the manuscript tradition based on some other locations for this text in the manuscript tradition (pp.705-708), and (2) that the body of the resurrection was not going to be “spirit” (as in disembodied), but Spirit-ed as transforming the body to be alive by the Spirit to the utmost.

The first of these issues was not something I found support for among other scholars and frankly questioned myself whether Fee might be overclaiming. Yet, some scholars have since found further support for precisely this sort of claim and I have come to be persuaded of Fee’s early claim (though this view still seems a minority interpretation of the data). The most notable recent potential support of Fee’s claim was an article by Philip B. Payne, “Vaticanus Distigme-obelos Symbols Marking Added Text, Including 1 Corinthians 14.34-5,” New Testament Studies 63.4 (2017): 604-625. On the second issue, the revolution in my own pastoral thinking and preaching shifted from a very spiritualizing notion of life after death to a very Spirit-ed notion of embodiment made right in Jesus at the resurrection (this happened long before I read N.T. Wright’s very helpful, Surprised by Hope). I found myself turned from ideas which owed more to Gnostic-like distinctions between “spirit” and “body” and to the Lord’s intentional redemption of all creation as very good. One thing that struck me in one of the recently published stories about Fee concerned him telling a class to not believe he had died when they hear about his death, but that he “is singing with his Lord and his king” [Editor’s note: This was also published in Regent College’s “Remembering Dr. Gordon D. Fee”]. This seemed both in line with Fee’s work on 1 Corinthians, that we live because he lives and we do not simply go to non-existence, but also disjunctive with Fee regarding the hope that has consistently been the confession of the church (and which Fee goes to great lengths to contend precisely for): we believe in … the resurrection of the dead. This is a hope not in our spirits dis-embodied living in a heavenly sphere after death, but in the resurrection of bodies that are Spirit-enlivened in every way at the return of the Lord Jesus to consummate God’s kingdom on earth as in heaven.

Gordon Fee’s name was such a household word among the Pentecostal pastors I found myself regularly engaging while pastoring and continuing graduate studies that we would regularly discuss his work with one particular highlight and turned-to-reference: God’s Empowering Presence: The Holy Spirit in the Letters of Paul (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994, 2012). It was this massive collection of exegesis of the Greek text of Paul’s writings followed by theological essays intended to articulate a Pauline theology of the Spirit that was part of the very inspiration for my own later PhD work (since published as) A Theology of the Spirit in the Former Prophets: A Pentecostal Perspective (Cleveland, TN: CPT Press, 2018). Fee’s attention to the nuances of the Greek text (grammar, discourse, TC, etc) and attempts at a cumulative theology of such drove me to consider how this magnum opus among his writings might be applied to other corpora of the Scriptures.

During my later graduate work, I read Fee’s newly published Pauline Christology: An Exegetical-Theological Study (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007) and found a potent articulation of early exaltation of Jesus in light of the OT revelation of Yahweh and Jesus’ unique revelation of the God of Israel (spurring my readings Larry Hurtado and James Dunn). This proto-trinitarian argument was an aid in considering the ways theology continued to develop not just into the NT, but into the earliest church who would only later give voice to a trinitarian confession and would do so as acts of worship. It served me well to seek to hear the texts of Scripture in their own contexts even as the Church was inheritors and proclaimers of that word seeking always to hear better what had once and for all been delivered. I was grateful to see that a more accessible form of this publication has become available for a wider readership in Jesus the Lord according to Paul the Apostle: A Concise Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2018).

While I have found many of Fee’s publications to be great aids to myself (even if only in spurring on further studies that move well beyond his own contributions), I would be remiss to not mention a particular aspect of Fee’s work with which I have found myself opposed. One of his most well-known writings (which has also spurred on numerous spin-off publications), How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth coedited with Douglas Stuart (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, originally published in 1981; Fourth Edition, 2014) finds its mention here at the end of my reflections, not because I encountered it after all of these other writings (it was his first book I read while in college), but because of my own critique of it. It also is not because it essentially espouses what some Pentecostal scholars might consider simply another Evangelical hermeneutic (which is reductionistic of Evangelical hermeneutics as if it is monolithic). When I first read this volume, I found one of the most helpful and accessible proposals for a Biblical hermeneutic that I had read to that point (his part being specific to the NT texts). It was only later while in graduate school and pastoring that I found myself pushing against his claims in one very specific area: historical narrative. Fee argued in this book, and at greater length in his Gospel and Spirit: Issues in New Testament Hermeneutics (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1991), that historical narratives (with Acts as the aim) were insufficient as Scripture toward developing theological claims because of lack of perceived authorial intent. This was a challenge to the Classic Pentecostal reading of Luke-Acts as setting a precedence and expectation of tongues bearing public evidence of this experience Pentecostal’s labeled “Spirit Baptism”. To be fair, my own rejection of Fee’s argument was not because of the Classical Pentecostal theological claims (which in my own estimation bear too many marks of a modernist epistemological impulse as influencing such), but because the Scriptures, OT and NT, are intended toward theological confession and worship as we find ourselves taken up into these words in adoration and conformity to the Word made flesh and now exalted at the right hand of God. My own contention is that theological intent is true not only of didactic texts (like Paul’s) but of narrative texts (like Luke-Acts, or the Joshua-Judges-Samuel-Kings as my own work contends). Roger Stronstad (who also passed away this year) was one of the most outspoken critics of Fee early on regarding Fee’s proposal (and their engagements at the Society of Pentecostal Studies remain the stuff of legend). It was the works of Stronstad which (for me) articulated the beginnings of a far more theologically defensible hermeneutic of narrative texts though I have traveled in yet other directions, see Stronstad’s, The Charismatic Theology of St. Luke: Trajectories from the Old Testament to Luke-Acts (2nd edition; Baker Academic, 2012), The Prophethood of All Believers: A Study in Luke’s Charismatic Theology (Cleveland, TN: CPT Press, 2010), and Spirit, Scripture and Theology: A Pentecostal Perspective (2nd edition; APT Press, 2019).

This critique notwithstanding, I am forever in the debt of Gordon Fee. He has inspired me to love the Scriptures as faithful witnesses to God’s self-revelation in Jesus. He has inspired me to seek to lovingly and faithfully follow God’s self-revelation even when it pushes against the norms of one’s theological and ecclesiological tradition. He has inspired me to be a faithful preacher and teacher, to pass on to others what I have received and to do so with words audible and written until all know and proclaim with the Spirit that Jesus is Lord.

Video Archives of SPS Honoring of Gordon Fee at AAR-SBL 2014

Blaine Charette, Mark Fee, Russell Spittler, and Murray Dempster (Blaine Charette chaired the special session)

Andrew Lincoln (shared by John Christopher Thomas)

Other Tributes to Gordon Fee

“Honoring Pentecostal Theologian Gordon Fee” by Rick Wadholm Jr

“Craig Keener on Gordon Fee, Giant of Pentecostal Scholarship”

“Michael Brown on Gordon Fee, Pioneer and Scholarly Role Model”

Category: Fall 2022, Living the Faith