Language Disconnect: The Implications of Bible Translation upon Gospel Work in Africa

One implicit reason, I suggest, for the non-use of African languages in education and other formal or modern contexts, is to avoid compromising the integrity of the language concerned. This integrity relates to its function amongst the living, but also especially to its function amongst the dead. European languages are pretty hopeless as substitute for the latter. European languages are obviously very powerful, and much prosperity can arise as a result of their sway. But the outside-dependency of European linguistic arenas is also glaringly obvious. European languages provide opportunities to be taken advantage of. They do not provide local foundations that can be relied upon. Local languages should not be corrupted! Any corruption of African languages that results in a failure to sufficiently please efficacious ancestors is dangerous to life and wellbeing. African ways have been and are definitely under attack from many quarters. All the more reason to do one’s utmost to maintain some order and sanity through the upholding of ancient (or even apparently ancient) indigenous traditions.

The Relationship between African and European Languages

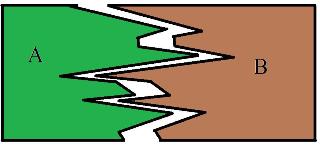

Figure 1. An illustration of two compatible languages.

Any relationship, or non-relationship, between African and Western languages can be illustrated diagrammatically. While diagrammatic representation has its limitations, it might communicate something helpful. My illustration would be better in three dimensions and with moving parts, but I am forced to attempt to make my point using two dimensional figures.

An illustration of two very compatible languages A and B is given in Figure 1. Their fit shows that when these languages come together (A moves closer to B), they will have a large surface of common functioning.

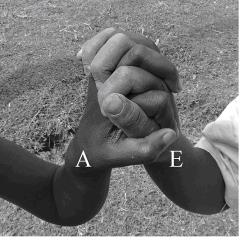

Figure 2. Two hands clutching tightly here represent mutually translatable languages, i.e. languages that move in harmony.

In Figure 2 I want to simplify Figure 1 above by representing A and E (African and European languages) as two hands, complete with clutching fingers, as in Figure 2. When either A or E moves (speaks), then clearly the other hand will move closely following the same pattern. Translation in this case will be accurate. This could apply for example to Spanish and Italian – similar languages used by neighbouring countries that have similar cultures.

Figure 3. Two hands that are less closely interlinked than in Figure 2 above.

The hands in Figure 3 are clearly not as closely attached. As a result movement of one hand may be less faithfully followed by movement of the other. The two languages here represented are related, but not closely, perhaps like Greek and Persian. Translation between such less closely related languages will be more limited.

Figure 4a. Hands that are much less closely joined.

Figure 4b. Hands that are much less closely joined.

In both cases of Figure 4, while movement of one hand will cause movement of the other, that movement may not be of the same direction, style, speed or type. These are distantly related languages, such as Greek as against the language of Aborigines in Australia. As movement of one had may not be closely mirrored by movement of the other in Figure 4, do unrelated languages may not faithfully be translated into one another.

In Figure 5 dissonance is very possible. That is, lack of contact between the two hands, mean that one hand may move totally independently of the other. Translation, i.e. faithful transfer of patterns of movement, may not be possible at all between these two hands (languages). This to me in many ways accurately represents the relationship between African and European languages. They can move in unison; but there is nothing obliging them to do so. They can at any time loose contact with each other, and move independently of each other.

Figure 5. Hands that are proximal but not touching.

In the case of Figure 2 above, a new language has become intertwined with a pre-existing language. Many German communities in America these days use English and are quickly integrating into the mainstream of American life. Figure 4 illustrates more distantly related languages (i.e. cultures). Simply working in unison takes more time and effort, but is not too difficult. That is to say, that translation is possible even if difficult. Fig 5 is especially interesting for us. There is little opportunity here for the two languages to work ‘hand in hand’ because they are simply too different. Hybrid languages such as Sheng[8] in Nairobi endeavour to bring such languages together. Unfortunately they generally please neither African traditionalists nor modern Westerners. Communities in which two such very different languages compete for attention while knocking against each other have some very peculiar properties. Their bi (or multi) lingual nature can be preserved for posterity! People of African descent living in North America seem to be an example. Although supposedly using the same language as the rest of America,[9] Blacks’ deeply different ways of life can continue to rub against a lot that is American.

Category: In Depth, Winter 2016