John MacArthur’s Strange Fire as Parody of Jonathan Edwards’ Theology, by William De Arteaga

Phariseeism has a long history in the Church Age, as practically every revival movement has had opposition from orthodox churchmen who have said, “This can’t be of God because it is too rowdy and different from what is normal.”4 For instance, The Wesleyan revival (1740-1800) is considered to have been among the most effective and transformative in Church history. Yet at the time it was bitterly opposed by churchmen of all sorts. One, Bishop George Lavington (1683-1762) was the most influential and constant opponent against Methodism. Lavington was offended by the Methodists hymns (now considered classics), outdoor preaching (now routine), and especially the “exercises” and “enthusiasm” demonstrated at Methodist services. He attributed these to psychological disturbances and demonic intervention—a sign that he was a true Pharisee who could not discern the move of the Holy Spirit in the Wesleyan movement.5

Pride in their theological traditions and opinions was a major characteristic of the New Testament Pharisees (Matt 15:2). This has unfortunately also passed into Christianity with various denominations posturing that their theology is ultimately correct, and deviations from which are damnable. I grew up in the pre-Vatican II Catholic Church which had this fault—we thought all Protestants, or almost all, were destined to hell. MacArthur’s brand of fundamentalist Reformed theology (young earth creationism, etc.) is quite similar in its sectarian prejudices. For instance, he believes a mark of the “heresy” of the Pentecostal and Charismatic Renewal is there willingness to fellowship with and accept Catholic Charismatics, whom Macarthur disdains as pure heretics (p .48, ff).

In full disclosure, this critical essay is written from the perspective of a charismatic Anglican priest with a Wesleyan perspective. As historian of church revivals I believe that the past revivals of the Church, such as the Great Awakening, and the Wesleyan revival, the Second Great Awakening, etc., greatly strengthened and enriched the Church.6

Now let me turn to the work of Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) probably the greatest theologian American has ever produced. He was a man like MacArthur who loved Reformation theology, but unlike MacArthur, had a grasp of Church history and a true understanding of the process of discernment.

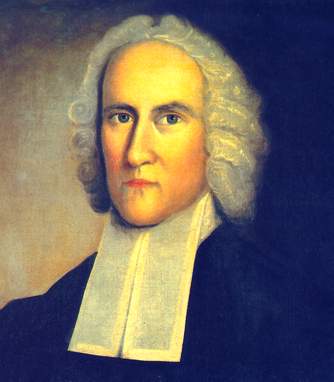

Jonathan Edwards discerns the Great Awakening

Jonathan Edwards

To understand Jonathan Edwards’ great achievement in establishing a discernment theology of revival we need to know something about his role in the First Great Awakening. A revival began in his Church in Northampton in 1734, which was triggered by a sermon series about damnation and salvation. The sermons led many to awaken from their nominalism to become truly born again and professing Christians. He wrote a letter to a colleague in Boston describing how it happened. This was then expanded into his first public piece on revival, A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton (1736)—now often called simply “Faithful Narrative.”

In this pamphlet Edwards described the process of conversion from nominalism into professing Christianity of several persons. This was a process of conviction of sin, despair at self-remedy through works such as prayer or good deeds and finally rest and release in receiving the salvation of Christ. The process at times involved outbursts of emotions.

Their joyful surprise has caused their hearts as it were to leap, so that they have been ready to break forth into laughter, tears often at the same time issuing like a flood, and intermingling a loud weeping. Sometimes they have not been able to forbear crying out with a loud voice, expressing their great admiration. In some, even the view of the glory of God’s sovereignty, in the exercises of his grace, has surprised the soul with such sweetness, as to produce the same effects.7

Edwards describes also how conversion and the presence of God affected the body in strange ways. Abigail Hutchinson, a person profoundly converted and sanctified by the revival, would at times faint away while talking of her experience with God.

When the exercise was ended [a “home group” meeting], some asked her concerning what she had experienced; and she began to give an account, but as she was relating it, it revived such a sense of the same things, that her strength failed; and they were obliged to take her and lay her upon the bed.8

The revival subsided by 1735, although the people touched by it remained fully converted. In 1739, George Whitefield, the great English revivalist, came to the colonies. Under his anointed preaching, revival became widespread—now called the First Great Awakening—with many of the bodily agitations, and emotional outcries becoming common.

Category: Spirit, Winter 2014