The Second Blessing of Spirit Baptism: British Reformation Roots of the Pentecostal Tradition

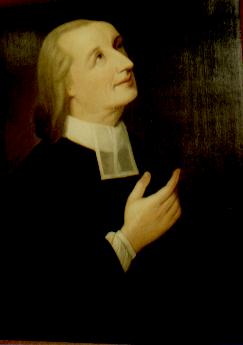

John Fletcher

The Holiness movement, including the Keswick Higher Life stream, is indebted to the theology of early Methodism. The Keswick movement began in England in the 1870’s through the work of Holiness leaders, notably the Quakers Robert P. and Hannah W. Smith. Robert and Hannah’s message gradually gained acceptance in the largely Calvinist-Reformed setting of seventeenth-century Britain. Keswick theology maintains with Wesleyan adherents a subsequent experience separate from the “new birth” (conversion); namely, the “fullness of the Spirit” or “higher Christian life” identified with baptism in the Spirit. The Keswick tradition defines Spirit baptism not primarily in terms of purification, but drawing from Fletcher, as empowerment for ministry; sanctification becomes a progressive experience transpiring over the course of one’s life. The Keswick movement appealed to Methodists and non-Methodists alike, opening the Holiness movement to Anglican, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and Baptist traditions.[11]

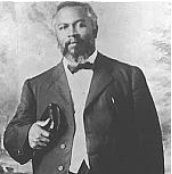

The soteriology of Pentecostal founder William Seymour also followed the Holiness trajectory crystalized by Wesley and Fletcher.

William Seymour

The soteriology of Pentecostal founder William Seymour also followed the Holiness trajectory crystalized by Wesley and Fletcher. Seymour identified sanctification with a subsequent work of grace beyond conversion that brought cleansing of the sin nature.[13] For Seymour, sanctification was necessary to receive the culminating blessing of Spirit baptism. Seymour considered Spirit baptism, not so much as a “third work of grace,” but as the gift of power to assist in the ministry of the gospel.[14] I close with the words of Charles Wesley, John’s brother, Methodist pioneer and author of some 6,000 hymns, who conveyed the significance of Spirit baptism for the ongoing life of faith in I Want the Spirit of Power Within:

I want the Spirit of power within,

of love, and of a healthful mind:

of power, to conquer inbred sin;

of love, to Thee and all mankind;

of health, that pain and death defies,

most vigorous when the body dies.

When shall I hear the inward voice

which only faithful souls can hear?

Pardon, and peace, and heavenly joys

attend the promised Comforter:

O come! and righteousness divine,

and Christ, and all with Christ, are mine.

Come, Holy Ghost, my heart inspire!

attest that I am born again;

come, and baptize me now with fire,

nor let Thy former gifts be vain:

I cannot rest in sins forgiven;

where is the earnest of my heaven?

Where the indubitable sea!

that ascertains the kingdom mine?

the powerful stamp I long to feel,

the signature of love divine:

O shed it in my heart abroad,

fullness of love, of heaven, of God.[15]

PR

Notes

[1] John Wesley, The Journal of the Rev. John Wesley A.M , edited by Nehemiah Curnock (London: Epworth, 1938), vol. 1, p. 476; see also Allan Anderson, An Introduction to Pentecostalism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 25; and David A. Womack and Francesco Toppi, Le radici del movimento Pentecostale (Rome, It.: ADI Media, 1989), pp. 98-101.

[2] John Wesley, The Works of John Wesley (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1959); see also Vinson Synan, The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition: Charismatic Movements in the Twentieth Century (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), p. 6. Actual sin is also known as “sins of commission” (p. 6); and Tony Lane, A Concise History of Christian Thought, rev. ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2006).

Category: Church History, Winter 2018