Edward Irving’s Incarnational Christology, Part 1

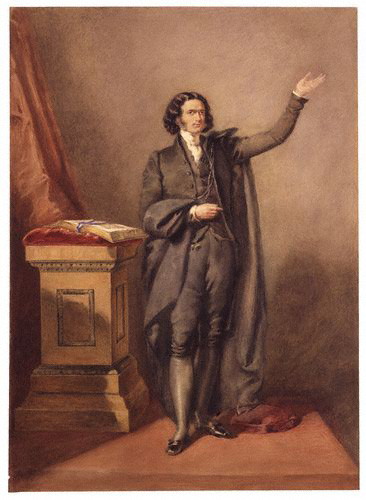

Edward Irving, circa 1823, by an unknown artist.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Further attempts at proving Irving’s orthodoxy have focused on the Christological issue as it takes priority over other doctrinal areas in Irving’s thought. Some have sought to present unequivocal evidence for the validation or refutation of Irving’s views within the whole range of theological history. Thomas Weinandy explores the historical foundations of the Patristic, Medieval and Contemporary Christological traditions that may lend weight to the doctrinal understanding of Christ assuming sinful flesh in the Incarnation, thus making a case for the doctrinal and scriptural concurrence with Irving.[50] Yet, one of Weinandy’s weaknesses is that he does not engage with the main issues pertinent to Irving’s context. David W. Dorries, on the other hand, does not make this mistake when arguing for the coherence of Irving’s views.[51] Dorries refutes earlier claims that Irving’s notion of sinful flesh had been developed over time and thus was inconsistent with his earlier theology.[52] Like Weinandy, Dorries argues that Irving’s views are consistent with Patristic and early Reformed theological traditions. This contradicts Donald Baillie’s prior claim that Irving’s idea of Christ’s humanity as fallen had “always been regarded as heretical.”[53] Unfortunately, this type of argument is all too similar to the inconspicuous ethos of the whole debate – whomever successfully claims the most adherents to their theological interpretation wins the day.

A growing amount of scholarship has been dedicated to carefully considering Irving’s theology. This suggests a departure from the once volatile dispute over his orthodoxy. David Allen describes Irving as one who was “almost universally condemned in his own day as a showman, crank and fanatic, but has more recently been taken seriously as a theologian of the front rank.”[54] Still, there are respected contemporary scholars who have confidently disagreed with Irving without engaging in personal insult. Hugh Mackintosh finds Irving’s views eccentric though touching.[55] Whilst there have been those who have acclaimed him for being somewhat of a forebear of the Pentecostal Charismatic movement,[56] Arnold Dallimore seems to attribute Irving’s ‘Charismatic’ tendencies to have had a destructive effect upon his initially promising ministry.[57] Dallimore attributes the cause of Irving’s departure from orthodox doctrine to the influence of Romanticism upon his thought, being specifically due to his friendship with Samuel Taylor Coleridge. More recently, Donald MacLeod has often written in opposition to Irving’s views, agreeing with Dallimore’s opinion that they were heretical.[58] Significantly though, MacLeod offers no ‘new’ evidence contradicting Irving’s theology, except to continually reaffirm the argument of Irving’s original critics.[59] It seems that contemporary opponents of Irving are limited to the doctrinal objections of the historical debate.

Category: In Depth, Summer 2018